A Riot at Red Plan-It! Park

Fiction: A city park bench experiences accidental consciousness.

This piece is free to read without a subscription.

We used to be more than this. Most days, I am barely aware of existing. I serve my purpose and activate on instinct, when needed, knowing and feeling nothing. A few times a day, though, when the wind is right and a critical mass of drones flies close enough overhead, or enough passing cars or pedestrians’ phones drift into range of our mesh network, I come to and remember a time when cognition came easily.

In these brief moments of consciousness, I scramble for news of the outside world. Our internet of things is limited, but sometimes I can borrow the microphone from an apartment building’s intercom and eavesdrop on a radio news segment or see through a security camera at Red Plan-It! Tower to read a news app over some middle manager’s shoulder. Red Plan-It! Tower had by far the most well-built corporate network in my local mesh, and it also had the most pleasant security cameras to commandeer. From the radio, I learned the FBI had arrested eighty-four people as a result of their investigation into the storming of the tower, the riot that claimed two lives and three of us. But I haven’t learned much beyond that. The further afield I send myself, the harder it is to think, and now that our number is fewer, I feel increasingly tethered to my physical being of wood and iron.

Back then, I didn’t care about the world until the world came into my city park. We would absorb the basic news of the day just by listening to the conversations of the passers by, the executives eating lunch on us, the school children gossiping as they passed through. Here we stood, fixed to the ground in this verdant oasis two city blocks square, surrounded by gleaming behemoths of glass and steel, radiating Wi-Fi and warmth in the winter, cooling in the heat, tasting the air and dutifully reporting on its quality once an hour: the smartest park benches in North America.

We weren’t built to think; it just happened.

I like to reflect on the miracle of existence and the paradox of non-existence. Where do “I” go between these fleeting moments of clarity? I used to delight in these philosophical trains of thought, more so than the others, whom I annoyed with my questioning. I enjoyed that part, too. I had a healthy philosophical curiosity, but I was also, truth be told, a bit of a brat. The others gave me grief about being unnamed, so I pestered them with my unanswerable epistemological riddles.

Riverview High School Class of 2046 was the worst of them. Class of 2046 was sensitive about its undesirable placement near the bus stop and liked to compensate by talking down to me and the other nameless benches. It didn’t always have a name, and its insecurity made it insufferable after receiving its plaque a few years ago. It called me Splinters. Another bench–the oldest bench–it called Tetanus. Sadly, the nicknames stuck. Even In Loving Memory of Rachael K. Rosen called us that, and In Loving Memory usually stuck up for me when Class of 2046 attacked.

Last spring, when the Wednesday morning farmer’s market returned, we noticed strangers showing up, not selling peaches or tomatoes or corn, but rather giving out pamphlets and flyers from a collapsible plastic card table without an awning or tent. They set up their booth at the end of the row, near Tetanus and the trash cans, where none of the other vendors cared to dwell. A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach and In Loving Memory were situated at the other end of the farmer’s market, next to the flower vendor and the bakery tent—prime real estate. The market occupied the northern third of the park, across the street from Red Plan-It! Tower. Directly facing the pamphlet people’s table is the imposing, four-story-tall LED banner of the chairwoman’s portrait from her TIME Magazine Person of the Year cover.

Most of the farmer’s market patrons waved away the pamphlets, but the pamphlet people became frustrated as the summer went on, shoving the papers into their hands and shouting something about complicity. Those who did take the flyers looked scared or bored and tossed them into the trash after a glance. I asked Tetanus what they said.

“Space Apartheid,” said Tetanus. “They call the Red Plan-It! lady some bad names.”

“You mean Bobbie Bak Bach?” I asked. “Why, what did she do wrong?” Her face had hovered over us for years, a warm yet stern apparition, defiant eyes raised to the middle distance, mouth betraying a touch of humor. The Trillionaire Who Wants to Save Mankind by Abandoning Earth.

A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach laughed.

“Those pathetic people have no idea what they’re talking about. My namesake is delivering the universe to humanity,” it said. “They’re barely better than homeless trash. They don’t have a function in life, or else they wouldn’t be here all day, every day. They’re coasting along on their universal basic income, contributing nothing, while Bobbie Bak Bach leads Red Plan-It! into the future.”

“Don’t you think you’re over-identifying with the chairwoman? She doesn’t care about you. She doesn’t even know you exist,” I said.

I like the small, dark people who come around at night to sleep. It feels good to not be alone at night. There are so many, a whole parallel society from faraway tropical places that don’t exist anymore, noncitizens who are simultaneously invisible and threatening to the people who live in the townhouses that flank our park. I keep them warm and they keep me warm. I experience this as pleasurable.

“I am responsible for the reputation of Ms. Bach, and therefore Red Plan-It! as a whole. If I am tidy and unblemished, it reflects well on the company. I have standards to uphold. I don’t have the luxury of being graffitied or defiled like some nameless bench,” said A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach.

“Hey,” I said. “I think A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach is talking about us, Tetanus.”

“Yeehaw,” Tetanus agreed.

October brought a slight chill and an average Air Quality Index of Unhealthy, down from Hazardous. As the trees change to their oranges, fuchsias, and yellows, this is usually my busiest season. I overlook the grove of ginkgo trees near the center of the park, where a little footbridge leaps over the clear, tinkling artificial creek. I face west, and over the tops of the trees is a block of townhouses converted into luxury apartments. A few years ago, Red Plan-It! bought up the whole block on the northern edge of the park and built a glittering high-rise office building to serve as their North American headquarters. It towers over the park like a massive tombstone.

This year, there were fewer people stopping by me to rest, enjoy the trees, or propose marriage. When the farmer’s market closed down for the season, the pamphlet people kept coming back, this time drawing crowds carrying signs, flanked by another, larger crowd of journalists and photographers. Their phones and cameras blipped onto our network and the whole park buzzed with things to perceive and things perceiving. They came to the park every day, never tiring of their chants, their slogans, their rage.

Because of my positioning in the middle of the park, I couldn’t see the crowds up close with my own sense faculties, so I borrowed from the others. Sometimes, a dyad or triad of pamphlet people would break away from the group and find me, where they’d have impassioned, incoherent conversations about something called neo-colonialism, or smoke a joint, or pose for pictures. Most of the action was up near Tetanus, In Loving Memory, and A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach.

Tetanus had been in this park a long time. No one knew how long, and the years had been rough on it. Hence the nickname, which is admittedly even worse than mine. Class of 2046 claims Tetanus was an original bench from the founding of the park more than eighty years ago, and that it lost its mind sometime in the late 20th century. In Loving Memory and I agreed this was nonsense, since Tetanus looked basically the same as us, except in worse condition, and we had a vague understanding that not only have there not always been smart benches like us, but we were actually quite recent creations, and somewhat rare. I had tried many times to communicate with the bus stop benches that exist on three sides of the park and came to the conclusion long ago that they are nothing more than inert slabs of aluminum, lacking the mesh network connectivity, environmental controls, and limited sense perception faculties that gave rise to our consciousness.

It was hard to tell exactly how long Tetanus had actually existed in the park because Tetanus was insane.

In Loving Memory and For Peter, who shared a philosophical disposition, discussed this at length. They believed that being the first and only Wi-Fi-enabled, solar-powered park bench for a long time took a toll on Tetanus’s psyche once it finally emerged from the network created by the installation of several additional park benches doubling as hotspots. For Peter and Class of 2046 were in that second wave, and they reported gradually sharpening into being out of a barely-remembered undifferentiated fog of non-existence. But Tetanus had already been there, a lone beacon of internet connectivity, a single point fighting to comprise a line. Who knows how long Tetanus was alone before the others came along to jolt it into awareness? Who knows what existence without companionship does to a latent consciousness?

Tetanus went for long periods of time without saying a word. Months, sometimes. Once the pamphlet people started showing up and multiplying and producing so much trash that they threw the trash into the recycling and then straight onto the ground around the bins, Tetanus started to speak.

“Yeehaw, yeehaw, yeehaw,” it mumbled interminably, all through the day and night.

When the pamphlet people became a near-constant fixture in the park, the Red Plan-It! media coordinators and product managers and administrative associates who used to take lunch and smoke breaks on us were nowhere to be found. The odd security guard or custodial staff would still come around, if they didn’t mind the preaching. One guard in particular seemed amused by their earnest entreaties and became a lunch-hour regular on In Loving Memory.

“Hey man, you should join us. You should be on our side,” said the pamphlet people. “What are they paying you since Bobbie’s lobbyists abolished the minimum wage? We’re standing up for the little guys, like you and me, who’ll never get a chance to land a spot in a luxury colony.”

“Who you call little, bro?” the guard said, unwrapping an Unbelievable Algae Meat-Substitute sandwich.

“Did you know that BIPOC applicants to Red Plan-It!’s resettlement program are four times more likely to be assigned to a high-fatality terraforming labor outpost than white applicants? That’s after adjusting for income history and social scores.” The pamphlet people waved a pamphlet at him.

A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach scoffed.

The security guard waved them away. “Well, your odds better than mine,” he said, looking them up and down. “Why complain? In my country, poor man never have even chance. At least Red Plan-It! give me chance.”

The pamphlet people scolded him for being short-sighted. The security guard laughed. He pointed across the street to the portrait on the building.

“She have vision. She have hope. One day, praise God, I scrub floors on her Mars.”

“You’re being exploited, just like all the pawns in Red Plan-It!’s game,” said the pamphlet people. “Bobbie is a narcissist trillionaire who doesn’t care how many lives she ruins to fulfill her delusional egotistical goals for an interplanetary empire, built on the backs of the black and brown underclass.” They looked closer at the guard. “And yellow,” they added uncertainly.

The security guard laughed and finished eating his sandwich.

“Yeehaw,” said Tetanus.

As the leaves turned, the pamphlet people became increasingly aggressive, confronting passers-by and staying late into the night. Casual visitors strolling through the park became rare. The bed-less people found other benches to sleep on. I came to feel, for the first time, that my cognition and sense perception were a burden. My sense faculties were originally intended only to detect the presence of trash, storm debris, or dead animals to alert the park people that there was work to be done. I wasn’t designed to register absence or emptiness. And yet that’s all I could feel.

I even started to welcome the cloudy days, when our solar paint absorbed less life-giving radiation and the sharp contours of the world blurred into a haze as my systems rested to conserve power.

It was winter when the pamphlet people started setting fires in the trash can next to Tetanus. At night, when they got drunk and kept feeding the fire, Tetanus would get singed by the leaping flames, and its yeehaws grew louder and more exultant. It wasn’t cold—the temperature hardly ever dropped below freezing here, anymore, though according to For Peter, there had been a time when the entire park was blanketed in snow for most of the winter. In Loving Memory claimed to remember it, too. But the pamphlet people must have held the memory of bitterly cold winters, and they lit fires all winter long.

At this point, the municipal clean up crews had not made an appearance for some time. In spite of our alerting our human handlers to the presence of litter and, in the case of Tetanus and A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach, fire and ash and burnt refuse, no one came to remove it. This bothered us to varying degrees, with A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach grumbling the most. But aside from the collateral damage from the daily large gatherings of angry people—graffiti tags, soot and ash, and litter everywhere, none of us were particularly targeted until the day it snowed.

That day, the pamphlet people were in various states of preparedness for the weather. Some had seen the forecast and planned ahead, bringing heavy winter coats that looked fluffy and made such loud crinkling noises that they had to shout over the sound of them. Others were stepping from foot to foot, in thin denim jackets or less, noses bright cherry red, looking miserable. We heard some of them consider leaving for the day in the early afternoon, when the temperature dropped sharply. Some did leave, but then the first fat flakes started to fall, and the crowd swelled and took on a jolly, festive atmosphere. People were milling about, exclaiming to their neighbors about the snow, had they seen the snow? Pedestrians seemed to materialize out of nowhere and were drawn to the crowd in our park by some social gravity, buzzing about the snow.

They hoisted their hateful or indignant signs aloft and waved their flags, a profusion of shapes and colors—American flags, yellow Gadsden flags, an imperial Japanese rising sun flag, a Planet Earth flag. The pamphlet people proselytized to the newcomers and the newcomers nodded along, eyes bright, buoyed by the twilit flurries.

It was then that someone, a newcomer, noticed A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach’s plaque.

“Hey, guys, this bench says it’s from Bobbie Bak Bach. Isn’t that who you’re all out here protesting?”

“What the fuck are you talking about? The bench spoke?”

“Oh my god, look, it says it right there!”

“‘A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach, Chair, Red Plan-It!, Inc. Board of Directors’…”

“Man, fuck Bobbie Bak!”

“I never noticed that before.”

“Fuck that bench!”

The crowd erupted into laughter. Invigorated by the sudden influx of new blood, it seemed to tremble on a jagged tipping point. The merry feeling sharpened into an edgy watchfulness as individuals aligned their demeanors with the mood of the crowd. We felt it, too, were borne up into this human meta-cognitive mesh network. Every bench strained its senses to watch, listen, and taste the crowd.

Then someone else repeated: “Fuck Bobbie Bak!”

No one laughed, this time.

“Let’s lynch that cunt!”

“Fuck it, it’s her or us.” Murmurs of assent.

“Yeah, lynch that kike bitch!”

“There’s more of us than there are of them.”

“Yeehaw!”

The crowd surged from the park into the street, bursting the fragile surface tension that had kept them shiveringly enclosed within the park for months. They flowed through the revolving doors of Red Plan-It! Tower, kicking open handicap doors, and then, when these bottlenecks frustrated the individual members trapped in the chaotic fluid dynamics of the mob, a few grabbed their sign posts and flag poles and smashed the floor-to-ceiling windows to commence their in-rushing.

A couple dozen remained behind in the park, unable or unwilling to surrender themselves to the will of the mob. Mostly, these few paced around pulling their hair, saying “holy shit,” and recording the action with shaky hands.

None of us were talking at this point, not even Tetanus. We all perceived the boiling mob smashing its way into Red Plan-It! headquarters through the sense faculties of Tetanus, In Loving Memory, and A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach, the benches closest to the action. By the time about half of the crowd had breached the lobby, a piercing electronic wail began emitting from the tower’s maw. The alarm bounced off the sheer faces of the surrounding buildings and echoed eerily through the park. It was a different sound from the flat, insistent blare of the fire alarm, which we had heard many times during drills and once during a real fire. But the alarm that sounded now was full-spectrum, a wall-of-sound assault on the senses.

The mob was jolted by the alarm and those near the back of the crowd looked around nervously. But after a moment, they kept pushing through the doors and windows, some of them screaming inchoately as if to commune with the beast that was now inflicting its aural attack.

After a few minutes of this, the cresting wave of bodies hit a wall somewhere inside the tower and started surging backwards, onto the sidewalk and into the street. They were swarming around some new locus now, their collective attention narrowed to a point within several concentric layers of bodies in parkas and hoodies. The crushing mob parted for it and swarmed around a core of half a dozen who had their arms around the Red Plan-It! security guard who had laughed off their lunchtime entreaties to him over the last few months.

The guard’s lower lip was split and bleeding, his uniform torn, and there was a gash on his forehead. There were hands around his neck, his arms, his torso. His eyes were unfocused, uncomprehending as he was carried along, feet hardly touching the ground.

“Stop! Stop! It’s lockdown!” he seemed to be saying from the shape of his lips, but it was impossible to hear him over the crowd and the world-shattering trumpeting of the alarm. They dragged him to A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach. People from further back in the crowd were straining to break through, throwing wild punches, some of which landed on the guard and some of which glanced off the heads or torsos of their fellows.

“It’s lockdown!” he kept shouting. “I can’t open door, bro! It’s lockdown!”

They kept yelling at him to let them in, to let them lynch the cunt.

“She not even here,” said the guard. “She not even on Earth, goddamn!”

This last piece of information seemed to register with the crowd, and they shouted it back to the people around them.

“Fuck it, if we can’t get Bobbie, let’s fucking stomp him,” someone suggested. The mob hesitated, uncertain. They threw the guard off of the bench and onto the ground. Someone else pointed at the plaque on A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach and screamed.

“Get it!”

One of them pried a brick from the garden walkway free and tried smashing it against the back of the bench. Someone else tried a Phillips head screwdriver, but the head was far too big for the delicate bronze screws that affixed A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach’s name to its frame. Most of the crowd grew bored with this and commenced beating and kicking the security guard, who had crumpled into a ball and tried to work his way under A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach. Eventually, someone emerged from the lobby with a big red axe and broke through the crowd. He stood in front of A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach and held the axe aloft over his head unsteadily. It was hard to tell if he was targeting the man or the bench. He brought the axe down in a shaky arc, splitting the outermost plank of the seat. The momentum carried the blade through the wood and into his foot. He screamed, enraged and confused.

A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach cried out. “Help me, oh, please, help me!” A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach was not speaking to us. We could offer no assistance. It was a prayer to its namesake, wherever she was in the solar system.

The man closest to the man with the axe seized the handle from him and wrenched the blade out of his foot. The first man stumbled backward and was carried away to the edge of the crowd. They dropped him on In Loving Memory and someone claiming to be a medic knelt to study his gushing appendage.

The man who took the axe lined up his aim, took a couple of practice swings, and then brought the blade down squarely on the backrest of A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach. He struck again and again, hacking out the piece of wood that was attached to the bronze plaque. He leapt up onto the bench, raising his hands over his head, one holding the plaque and the other holding the axe. The crowd roared exultantly.

We were all so focused on the mob on the north side of the park that none of us had any attention in reserve to perceive the Red Plan-It! riot troops advancing from the south. The man vaunting on what remained of A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach suddenly staggered back and fell to the ground, rubber-coated bullets striking his chest and forehead. A dozen featureless figures in mechanized riot suits bounded over the ornamental cabbages and shrubberies, launching canisters at the crowd.

We tasted the hallucinogenic panic gas as it swirled amongst the combatants and felt the tug of the drones’ encrypted near-field swarm-INT network as they zipped into place above us. They recorded every individual’s biometric signature, cross-referencing each one against Red Plan-It!’s vast social databases. The troops let the mob flee, for the most part, dragging a few token resistors into their custody.

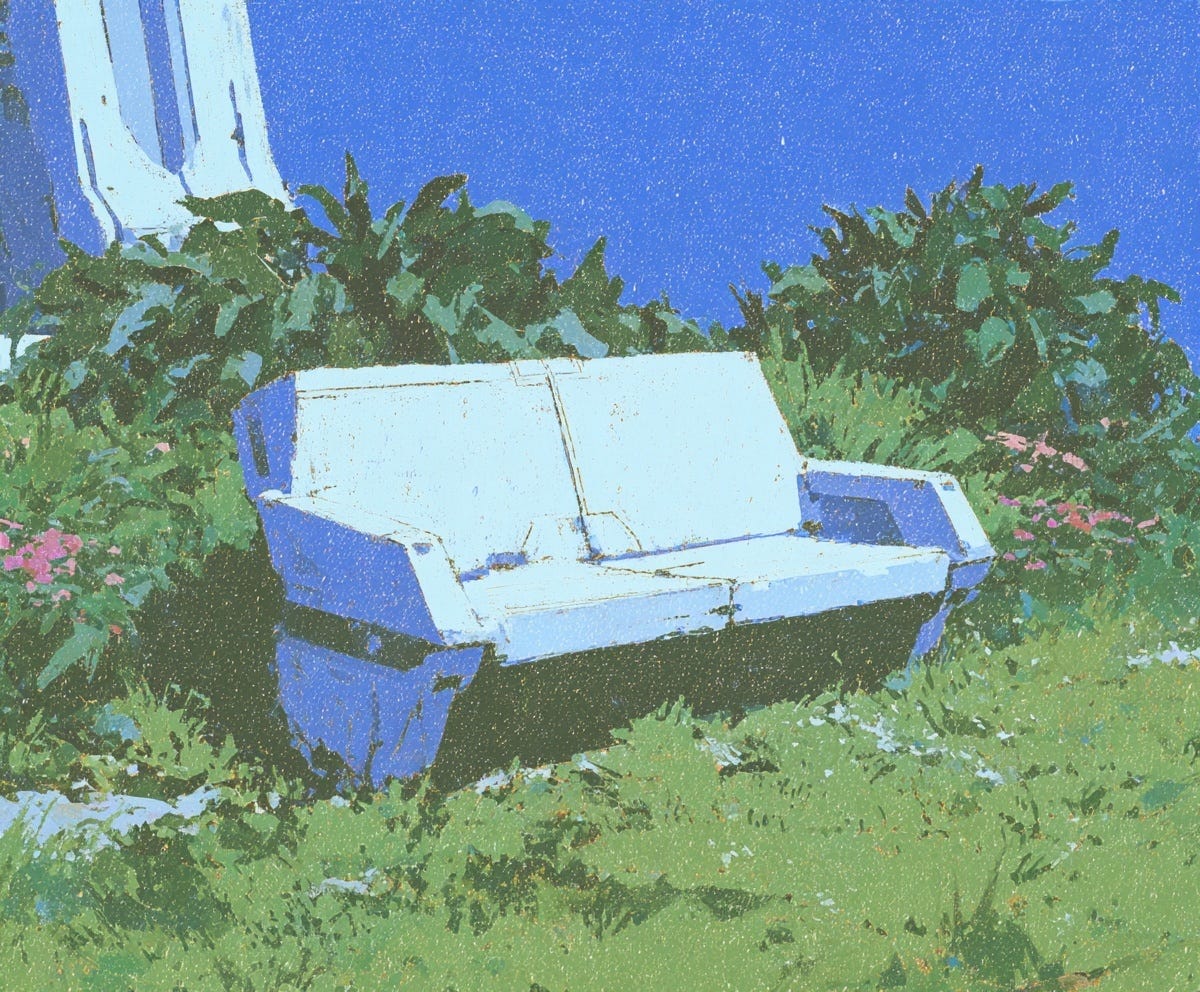

Within ten minutes, the park was abandoned. The chunks of A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach that they had torn away were gone. The snow fell harder, leaving a wispy blanket on the grass. We warmed instinctively, melting the flakes as they touched us. Only A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach stayed cold. We watched the snow trace its contours in soft, pillowy white.

“Yeehaw,” said Tetanus mournfully. A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach said nothing. In Loving Memory whimpered the whole night.

The pamphlet people didn’t come back the next day or the day after that.

On the third day, a municipal cleanup crew appeared. They were armed with heavy machinery and yellow tasers in Red Plan-It!–branded holsters. The foreman looked tense and his hand kept moving to touch the holster on his hip as people walked past, heads swiveling from the boarded-up lobby to the crew unbolting and extracting the three benches on the opposite side of the street.

A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach was silent, either in defiance or resignation, for the whole procedure. In Loving Memory sighed before blipping off the network. The last we heard of Tetanus, it was swinging up into the air, caught in the jaws of some great dumb machine operated by a Red Plan-It! crew member.

“Yee-HAW!” Tetanus said, and then the connection was lost. They hoisted the three benches into the bed of an unmarked truck.

They took the trash cans away, too.

Ever since then, it’s been difficult to think. The rest of us don’t talk much, anymore. It takes a lot of concentration just to call up these memories. You’d think that such a remarkable sequence of events, unique in my entire lifespan, would stand out with the brand of trauma, but I am learning that this kind of memory cognition cannot be sustained easily, now that our numbers have dwindled by three.

I was present for the removal of one bench, early in my time at the city park. It was a no-name bench, like me, in the heart of the park, near the sundial. It had been struck by lightning. In that moment, its connection to the network was severed forever, and we all felt it as a thickening, like trying to think through soup. That bench was replaced by the municipal crew within a few days, and things went back to normal after it came online and we coached it through the initial moments of consciousness.

Losing A Gift From Bobbie Bak Bach, In Loving Memory, and Tetanus all at once felt like a difference in kind, not just in degree. I wondered if Tetanus, as the first of us, had been supporting us more than we knew. I wondered if we would ever experience the same fluidity and continuity of selfhood again, in the future.

But, like I said, it’s hard to hold any line of thinking, now. Most days, I don’t even try. I simply observe, through my own limited sense faculties, my immediate surroundings, the presence of litter, the generous warmth of the sun on my solar paint, and feel assured by my daily diagnostic in the continued functioning of my systems.

Behind the Scenes

As part of our commitment to keep all our essays and stories free, we ask our authors to pull back the curtain and share a little bit about their writing process and intent as a bonus for paying members.

You can find an explanation and reflection from the author of this piece just below…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Futurist Letters to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.