Criers and Kingmakers

A response to Ross Barkan's "The End of Prestige" on how it's never been about the prizes.

In 1992, Cormac McCarthy—obscure and impoverished—released All the Pretty Horses. His most accessible work yet, it won him the National Book Award, the recognition of legacy media publications, and 190,000 hardcover sales. This was his ascent to the mainstream. You may understandably conclude that the reception of this award and subsequent increase in sales and notoriety presents a clear contrast between the literary ecosystem of the day and the current state of affairs. You would be wrong. Literary ‘stars’ are not and were not created by the highly insular and oftentimes mercurial literary community. Were we to rank the people responsible for McCarthy’s present-day status, the National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize committees would be fighting with Harold Bloom for a distant second. Oprah Winfrey stands alone in first.

Let us reflect first on how things haven’t changed. If one were to consider the Pulitzer of old to be a moneymaker, surely it would still be such today. I would point toward successes like the 2010 novel Tinkers, which sold nearly 400,000 copies in the two years following its Pulitzer win; or the more recent winner, Viet Thanh Nguyen’s The Sympathizer, which sold 400,000 copies in the year following its 2016 Pulitzer win and was adapted into an HBO miniseries. The data here is in the prize’s favor, given Sympathizer had moved only 22,000 copies prior to the win. These prizes are doing exactly the same work they have done since the eighties—that is, signaling to the literary community (those who have not self-selected into reading only romantasy or only pulp science fiction and fantasy) that this new author is worth your time and money.

True literary royalty, though, is and has always been made outside the literary world. Let’s look at Cormac McCarthy’s real star-making role: an interview with Oprah Winfrey. Allow me to suggest that the current centrality of the late McCarthy, as well as the millions of copies The Road sold, is not to be credited to his National Book Award in 1992 nor his Pulitzer Prize in 2007, but to his inclusion in Oprah Winfrey’s Book Club and subsequent interview, a process that to this day sees writers like Colson Whitehead ascend into stardom. Oprah selected The Road for her book club before it won any significant prizes, and McCarthy then deigned (contra the great Jonathan Franzen) to appear on her show. This is the cleavage between Cormac McCarthy and Annie Proulx, Stephen King and Clive Barker. It is not this internal “literary machine” that produces stars; the machine places writers at its forefront and hopes the mainstream picks them up.

This was the power of Charlie Rose. If you have a writer from the ‘90s you like, then in all likelihood their most popular media appearance is from The Charlie Rose Show. You and I might be led to believe that all this man ever did was platform the great writers of the day, but the wide reach of The Charlie Rose Show actually came from its breadth of subjects. He’d interview CEOs and actors alongside philosophers and academics. So, when he brought an author before the audience of hypercurious dilettantes he’d cultivated, that audience would spread the word among their friends. Charlie was a totem, a symbol of the monoculture we once had, a force which created lasting fame for guys like Kazuo Ishiguro—who would not be so grand a name in either the 1920s or the 2020s.

This doesn’t, however, need to become another lament for the loss of a monoculture. You can still bring an author in front of millions of people—just put him on The Joe Rogan Experience or The Lex Fridman Podcast. Now, one may look at the comparative paucity of fiction writers on those shows as representative of the form’s dwindling place in the culture. I would counter that the preponderance of tech bros and martial artists represents only the intellectual narrowness of the hosts. When Ross Barkan writes in “The End of Prestige,” “The establishment means well, but it’s frail. It cannot birth stars like it once did; its anointment powers have dried up,” I think, well, how do writers get on major platforms? In my experience on the marketing side of tradpub, it is much the same process as before. Review copies are requested and sent, popular authors in the genre are notified, major legacy media publications choose whether to run a review. Whether that author is elevated into the zeitgeist and finds himself on Lex Fridman is a dice roll. Publishers do all they can to saturate the minds of people already plugged into this small slice of culture, but beyond that you live at the whim of Oprah Winfrey and Call Her Daddy and always have.

Maybe this stings in a world that is still struggling to understand that there’s no meritocracy and there never has been. Just ask Jonathan Franzen if Oprah’s selections were purely merit-based. The Pulitzer Prize has supposedly always done its best to select the best works of literature in any given year, but somehow for the last ten years it’s been saying that no young, straight, white male is deserving of top honors. “Well,” you may say, “Surely this means it’s lost its way and no longer adheres rigidly to merit as first-pass criteria.” What follows, then, in this line of thinking? A great diminishing in importance. Thus, “prestige no longer matters.”

Barkan says he isn’t making an identitarian argument, but his writing is downstream of it and exists because of it. It leans on the just-world fallacy. The reality, though, is that these prizes have always been a little ridiculous and often unfair. See the Pulitzer refusing to crown a winner in 2011 and 1974. See also the Nebula Award refusing to accept Pynchon’s work as the best science-fiction novel. See the great (and, in my opinion, disrespectful) clamor surrounding John Steinbeck’s receipt of the Nobel. If you’d like further insight on how internal politics has always muddied the awards selection process, see the strong-arming T. S. Eliot did in order to get Ezra Pound the inaugural Bollingen Prize.

We must acknowledge two things: that the current-day cult of letters is small, and that it essentially always has been. Things created for its benefit will necessarily always be as niche as literary fiction itself. I will invoke Caleb Caudell, as Barkan himself did, to make the point that the people who kept a mental inventory of Stegner Fellows in 2004 are the same kind of people who keep one today. With respect to the great Ottessa Moshfegh (whom I could name off the top of my head), the average person has never been greatly familiar with its recipients. The New York Times “Notable Books” list has similarly only been relevant to the literary leerers (and the agents of the authors selected).

Did you really think DFW’s “Great Male Narcissists” shook the monoculture? One of the most significant Baby Boomer authors pens a devastating teardown of John Updike and the aftershock is a Slate article. You grew up dreaming of being an A-lister with six Pulitzers pinned to your lapel not because this was a real thing, but because you were too young to know better. Some, like Sean Thomas, would say that literary fiction is not only niche, but that it was an unnatural blip, a brief anomaly that ought not to have even existed. I’m not arguing nothing at all has changed since the 20th century. Rather, in our collective rush to eulogize the literary establishment we have misplaced the locus of star creation, and with this error all further steps are misplaced. In our critiquing of contemporary literary culture we have jumped to prescribing cures for the supposed problems, but I do not believe we have succeeded yet in describing the sickness.

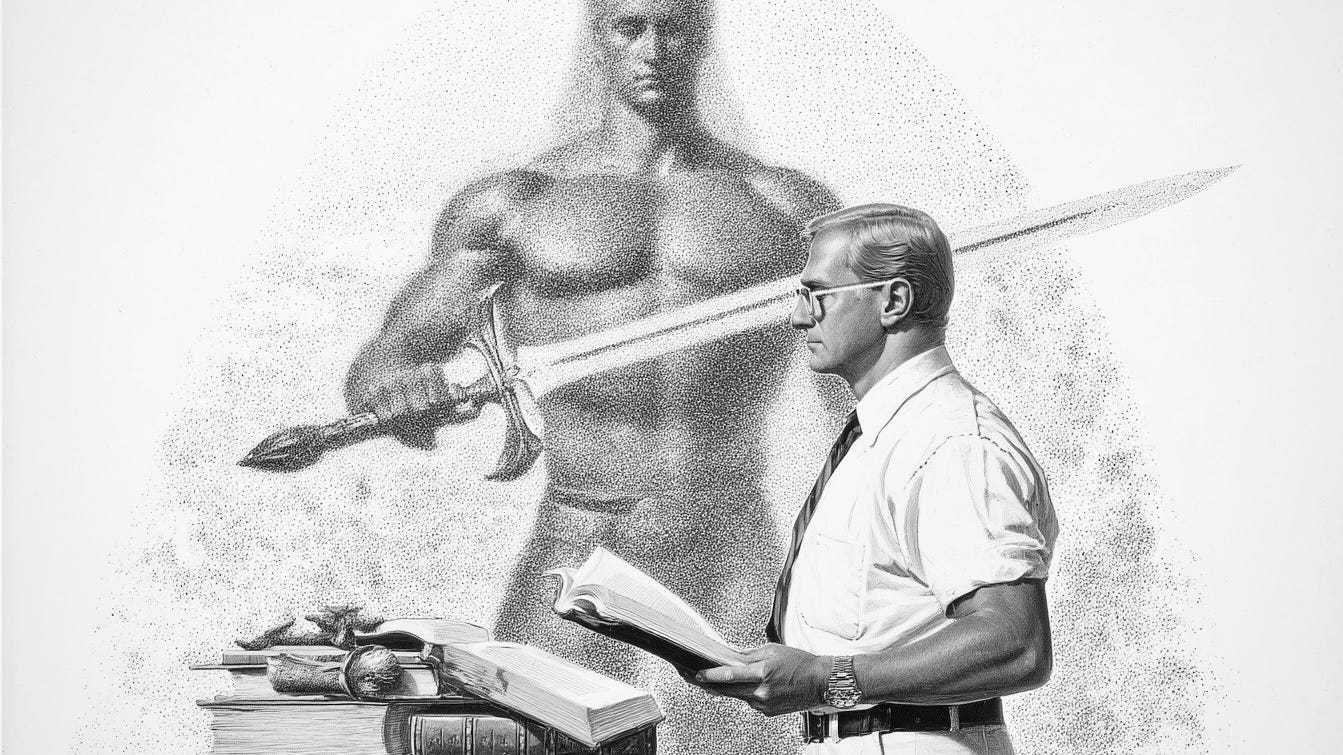

There’s a good call to action at the conclusion of “The End of Prestige,” but its idea isn’t so novel as perhaps the writer thinks. In the early 2020s a group of male writers asked themselves the same questions: whatever happened to the Michael Moorcocks and the Gene Wolfes; where are the snows of yesteryear, the big man with a sword on his hip and a beautiful woman on his shoulder? The Iron Age movement sprang in response to this. These creators, however, mostly sell to their friends. That network of friends is certainly robust, and there are impressive projects coming out of there, but it is not lost on me that the best-sellers also have huge YouTube channels or X accounts. And maybe I’ll be so bold as to say that creators like Razörfist and Shadiversity are not fulfilling the duties of their station; they are failing to do the job Charlie Rose did so faithfully for twenty-five years (before all the stuff came out about the sexual assaults).

And it has to be platforms like Razörfist, and not the numerous high-quality book reviews like The Art of Darkness pod or The Side Bar or the show I used to cohost, The Unreal Press Podcast. These shows will always be narrow in scope, appealing to people who are already predisposed to engaging with the literary arts. Better that the male-centric equivalent to Call Her Daddy starts inviting the likes of Ross Barkan or Joshua Cohen. This requires an exceptional effort, by the way. There’s a reason that Reese Witherspoon has one of the only notable celebrity book clubs. It requires the person (or their publicity team) to make the specific effort to read and then platform authors. I would champion creators like Wendigoon, responsible for making the Cormac McCarthy subreddit unusable and ballooning the Amazon bestseller ranking of The King in Yellow. PewDiePie before him introduced many current lit-bro staples to a new generation of young male readers. Neither of these creators is first and foremost concerned with literature. It’s simply one focus in a wide range of content. People come for ‘let’s plays’ and creepypastas and stumble into literary discussion.

Scribner hasn’t a thing to do with it. Neither does the Pulitzer Prize committee. It has never been automatic. There was never a time when you won the Pulitzer and the next day found yourself on every TV in America.

Ross Barkan’s proposal is admirable. He asks us to sit down and write. Block out the noise, drown your dreams of prestige, and grind word count. But this to me reads as a failure to truly engage with the literary paradigms of the past versus that of today. It’s a resolution to go about as if you are living in a post-apocalyptic literary wasteland, when there are, as I’ve mentioned, the same ways of “getting big” as there always have been. That star-making mechanism you ascribe to the old literary machine was not actually controlled by the Pulitzers, PEN/Faulkners, and Bookers any more than it is now.

So, go to that Great American Novel (another coinage from forty years ago that has entrenched itself in the culture of letters and given writers all kinds of strange ideas) with a Pulitzer in mind. Don’t let any sadness enter your heart because it doesn’t mean what it did in the ‘90s. It does. You will receive laudatory articles in The New Yorker and The Times and The Post. You’ll be the subject of a crossword clue. You’ll receive a bit of cash, and a small subset of people will flock to your book in similar numbers to thirty years ago. However, whereas in 2007 it may have been sufficient to a charm a few daytime talk show audiences, if you want an invitation to 2025’s Eyes Wide Shut masquerade then consider writing a novel about Brazilian jiu-jitsu.