Current Affairs

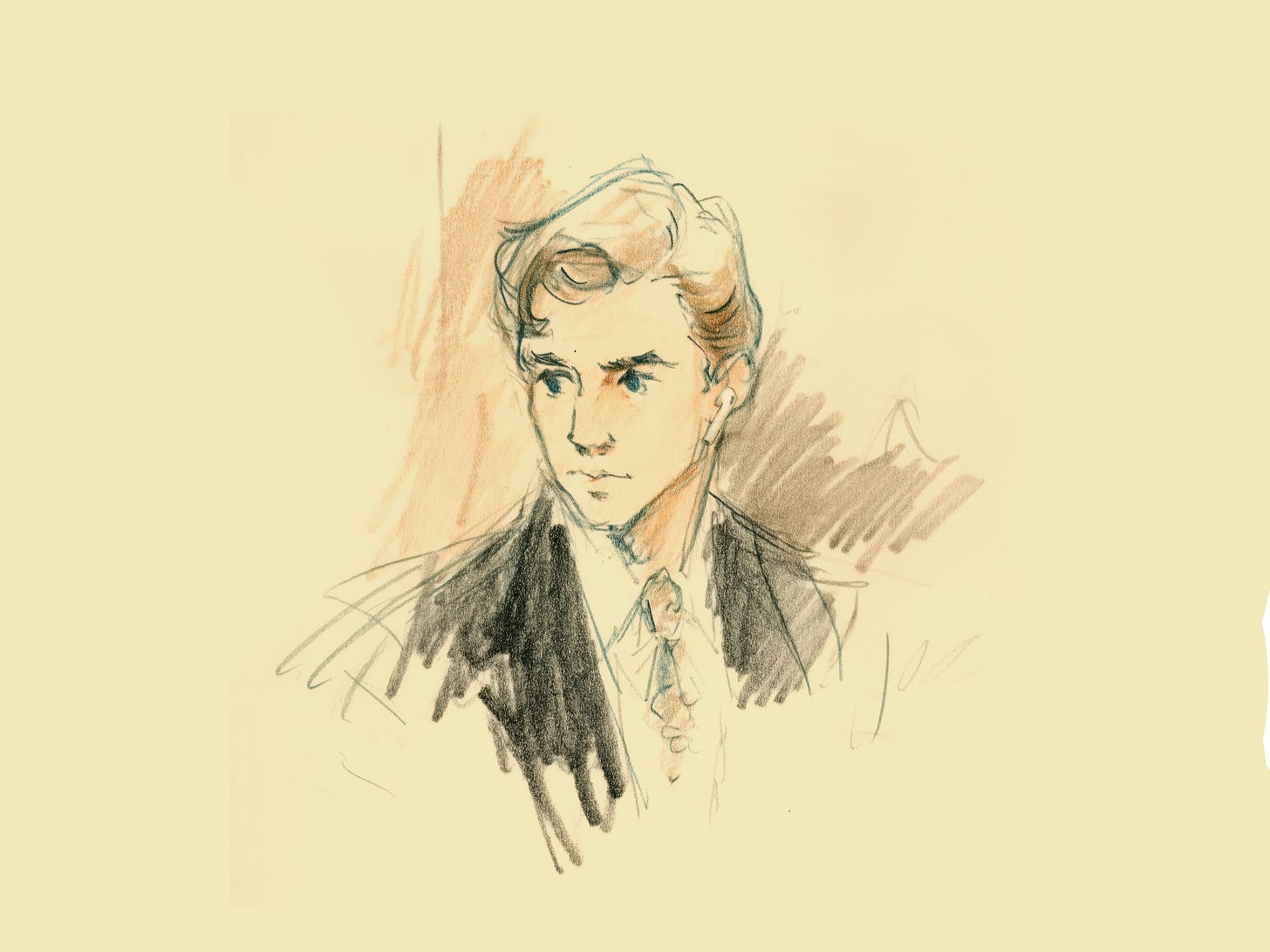

Fiction: The first chapter of the new novel from Cairo Smith.

This is the first chapter of the novel Current Affairs by Cairo Smith, available now in digital and paperback editions.

Current Affairs is a contemporary novel of love and young professional ambition. It follows ten years in the life of a Midwesterner as he sets out to make his name in Manhattan.

This piece is free to read without a subscription.

1

Calvin Munn removed his tie and felt stupid on the veranda of the Kaihoa Resort. All his clothes were fit for a New York autumn, and in the humid heat of a Honolulu December his shirts were soaked through in thirty minutes flat. He felt unserious without his tie, like a tourist, or worse still an Angeleno. Despite this, removing it was the more respectable alternative to sweating out a starched mainlander collar.

He knew one of two uncomfortable fates awaited him. He could not go on living out of a horribly mispacked Samsonite. He could either buy sloppy local clothes, betraying his Manhattan dandy’s pride, or he could dress in local aloha fabrics and look even more like a haole with too much money to blow.

He was a haole with too much money to blow, and that reality only made him more embarrassed by his misery. It was a humiliating thing to be rich and full of ennui. It made him feel like he might as well give it all out in some African village and call it a day, but it was not his money to spend. It was Rebecca’s, which meant it was her father’s, and this was the lock on the golden shackles that had kept him chained to the railroad track of life these past five years. At some point, maybe in a few months now, he knew the train could come.

He rolled the magazine in his hands up into a circle, as if preparing a final swing against the pitcher with one strike left. Then he let it fall into the trash can next to the railing overlooking Waikiki. He had hung onto the magazine, uninformed on the new Pacific situation as it was, for two reasons. First, he had learned there was no recycling in Hawaii, and the Millennial-raised goody two-shoes in him was loathe to put paper in the trash. This was an irrational tendency, like that of an ex-Catholic who still crosses himself before the Virgin, and it persisted no matter how many articles he read about recycling being mostly a hoax.

The second reason was that he had filled the inside cover with desperate, maddened confessions of the heart. “I love you. I’ve always loved you. I’m obsessed with you. I would throw out everything in my life for you. Just say the word. I’ll be there.” These lines had been repeated in scrawl between the bylines and copyright warnings of the American Defense Quarterly masthead. Three canned Mai Tais had eased their coming, and the dimness of his hotel suite lamp at three a.m. had helped him write without truly facing the words on the page.

Now, in the light of a clear Hawaiian afternoon, a fear gripped him—the fear that the words were just mania, just desperation, just the ravings of an unhappy mind looking to break from the golden shackles and stand tall. It was the fear that it was all about him, and not about her.

Calvin was glad to be free of the stress-crumpled magazine when she approached. The woman, the object of his ravings, was his age, twenty-eight. In fact, she was his age exactly, give or take a few minutes. She had been born in the same hospital, on the same floor, and it was likely that in the plastic tubs of the ward she had been one of the first human beings he had ever seen. At least, he had thought that for a while, before learning babies are born so blind that he most likely never saw her at all. Still, he had heard her cry, there and in years after. He held a secret room in his heart for every place and time he had ever heard her cry.

The two young people, children of Iowa born into Dubya’s twilight, stood on the veranda on the mutual precipice that was the coming start of their thirties. “Hello, Madeline,” he said. He loved her name. He had loved it when it was Madeline Alder, and he loved it even now with the unfortunate Payne attached. He loved it so much, he had drawn it a hundred different ways, like those shape poems they’d tried to drag out of him in undergrad English. ‘Concrete poems,’ he suspected they’d been called. In his mind, they weren’t concrete at all, but honey and goldenrods and everything alive in the world.

Madeline held her hands together at her waist and watched him think all these thoughts with a closed-lipped smile. There was no need to explain his slowness of speech to her, because he knew that every fleeting thought would make its way to his expression and be seen. She was slim, tawny-haired and pale-skinned, with a hint of Castilian royalty way back and the rest all Iowa corn stock jumbled together. From certain angles, she looked almost boyish, on account of the sharpness in her bones. From others, she was the most beautiful woman Calvin Munn could possibly imagine.

“Hi, Calvin,” she said. There was a softness in her voice that made all the other sounds in the world go hushed, like someone was pulling the ambience slider down on the enormous production mixboard of life.

She waited for him to speak next. The paradox of their relationship was that he had known her for ten years and change by the turn of the sun, hundreds of hours by text and call, and only five honest days face-to-face in all that time. This would be the sixth.

“I’ve really screwed things up,” said Calvin, keenly aware of the sweat stains under his sleeves. He was half a head taller than her, well-cut and fair from hairline to toes, although three weeks of tropical sun had been doing aggressive work on his complexion. He squinted out at the glaring horizon, a touch hungover, and wished he had either a drink or dimmer view as balm. Madeline was one of the few people with whom he wouldn’t wear his signature thick-framed ‘fed’ shades.

“How so?” said Madeline.

“I packed all the wrong clothes, for one,” Calvin sighed. “That, and, with this whole Rebecca and Imogene thing. I don’t know. She was bawling her guts out to me this morning—Imogene, not Rebecca—and I just realized I’d read the whole thing wrong. I’ve been selfish. Worse, I’ve been a coward.”

“Yeah,” said Madeline, speaking sparingly not from disinterest but from a desire to be delicate. “It’s tricky. I can only imagine.”

“Well, you’ve had your own, you know, whatever,” Calvin started, and finished the sentence with an unspecific gesture. He alternated between staring at her eyes and the reflection of the sun, choosing the latter when the intensity of the former grew too overwhelming. “I know it’s not the same.”

“Nothing’s the same as anything,” said Madeline. “Yet it all seems sort of familiar.”

“Maybe we should—” Calvin began and hitched to a halt. The words he’d been holding back for ten years would certainly not come easily now.

She sensed the turbulence in him and cleared her throat. “I have something to tell you,” she said, leaning on the railing and facing outward to the sea to mirror him.

He looked over at her, and from the tension neither good nor ill in her eyes he somehow knew what it was. He had known it was possible, that it was natural, even expected, and yet in the oppressive heat of that winter afternoon it somehow cut straight through him and broke his heart.

Ten years earlier, Calvin was a boy in Chester, Iowa. He was just as tall, about forty pounds lighter on muscle, and his main concern in life was the upcoming release of the PC historical strategy game Civilization VII. After that was his gang of gaming friends, then Domino’s Pizza on the nights when his mom wouldn’t cook, and then a mercurial stew of demands with schoolwork somewhere near the bottom. The lower ones frequently shifted and squabbled, but none seemed poised to dethrone either the boys or the upcoming Civ. That is, until the girl on the grassy hill came into frame.

She looked like Christina’s World, and Calvin loved Christina’s World. He loved Wyeth in general, although he sometimes found him spooky. He had decided that past fall in AP Art History that Hopper’s oeuvre was his favorite overall, but Christina’s World was unbeatable as a single painting. This enthusiasm persisted even after classmate Aspen Kessler informed him that Wyeth and Hopper were basic, and that he needed to expand his taste to Eastern painters for a more worldly balance. He did not realize until many years later that she had been trying to flirt.

For five months, Christina’s World had been the first and last thing Calvin saw in a day, since he had made it both his PC lock screen and desktop. The painting graced his 4K monitor as if the two were meant for each other, filling its glowing pixels with the warm tones of a mowed Maine hill and a thin young farm girl lying atop it. Two months had gone by before he noticed the extreme thinness of her limbs, and upon Googling he discovered she was meant to be weakened with some disorder. He supposed this was meant to unsettle the viewer, as Wyeths often did, but it only made him love the whole thing more. He didn’t just love Christina’s World, he loved Christina, and he would love her even if he had to carry her all the way back to the house in his teenage arms.

One night, after a particularly frustrating round of Civ VI, he had quit the game and found himself facing her golden hill once more. One thing he liked about his choice of wallpaper was that it compelled him to keep his desktop relatively tidy, out of respect for the girl and the composition. He stared at the image, eyes fried from hours of failing to conquer the Romans, and decided he would strive to one day see the painting for real.

That was what he had decided to open with, trudging up a hill just past lunch to see why a denim jacketed girl was lying atop it. “Hey,” he said to the stranger, taking long strides. Pointwestern High was just large enough that you could make your way through and not know everyone. “You know Christina’s World?”

“No,” said seventeen-year-old Madeline Alder. She was all the dimensions of beauty Calvin would see on that Kaihoa veranda, just younger, like the weight of living had not yet burnished the adolescence off her face to leave polished cheekbones behind. Her gaze drifted from the distant steeples and big box stores of downtown to Calvin Munn. She looked vexed.

“What?” said Calvin. He had never expected vexation on the face of Christina.

“What what?” said Madeline. “Shouldn’t I be the one saying, ‘What?’ You’re interrupting.”

“Interrupting, uh, what?” said Calvin, helplessly.

“I’m ruminating,” said Madeline. “Deliberately away from people.”

“Oh,” said Calvin, and thought up an excuse. “I just thought you should know the bell rang. Lunch is over.”

“Are you a yard duty?” she asked. It was rhetorical.

“I’m Calvin,” said the boy. He was either too meek for how tall he was, or vice versa.

“I know,” said Madeline, to his surprise. She gave up on supine-lateral rumination and sat up. “You had a locker above my locker for a whole year. Your backpack straps would always hang down and it was so annoying to have to bat them out of the way to not shut them in mine.”

Calvin shrugged. “If you had, I guess I woulda had to wait for you to come back and open it, and then I would remember you for sure.”

“So, my fault for being so polite I’m forgettable?” said scowling Madeline.

“Well, you’re making up for it now,” Calvin teased, and sat cross-legged beside her.

A warm spring breeze wafted over central Iowa, first touching him and then her. “The bell rang,” said Madeline, nodding toward the empty high school yard. “Better get to class.”

“When I’m done ruminating,” said Calvin, and picked a dandelion. “Flower for your name?”

“That’s a weed,” said Madeline.

“It’s a wildflower,” said Calvin, “and with every second I don’t know your name I am more and more inclined to just make one up.”

She gave him her name, and then asked what Christina’s World could be. Their conversations would always and forever circle through topics that way. Calvin once described it as a series of layers, but it was really more like an Elizabethan couplet, with A and B and so on and so forth coming back around in turn. For a clever seventeen-year-old unused to repartee, it was both a workout of acuity and a thrill.

“It’s a painting,” said Calvin, “and I wanted to tell you, you kind of looked like it, sitting up here on the hill.”

“I thought you wanted to tell me to get to class,” said Madeline. She had black corduroy pants and a white shirt under her jacket. Her small feet wiggled with a kind of idle energy at the ends of her crossed legs. She wore gray Vans and low socks that let a hint of bare ankle shine.

Calvin, shocking even himself, looked down and imagined her sneakered feet on his lap. He imagined putting a hand on her corduroy-covered calf, continuing their conversation here on the hill until school let out and they made their way back to the bus lot. He hoped she couldn’t see this sudden image laid out on his face.

“I can want to tell you multiple things,” he said. “Jokes aside, sorry about the backpack straps.”

“It’s okay,” Madeline laughed, and then immediately started another complaint about it. “I even yelled at you one time, as you were walking away, ‘Put your stupid straps up!’ but I think you had your AirPods in.”

“Probably Bladee,” said Calvin, and wondered how many other foul or fair remarks had been lost under the din of Swedish rap.

“Hah,” said Madeline, like she was remotely cool, like she had even the faintest idea what Bladee could possibly be. Her Spotify Wrapped the three years past had been a towering tribute to Sofia Wolfson, Samia, Lucy Gaffney, and a dozen other sad girl indie darlings.

Calvin was not known for being forward at Pointwestern, but something about the spell on the hill made him feel like he had left high school behind and entered a painting all his own. He would later learn this spell was simply the Madeline Alder effect, and it would reliably recur whenever the two were alone in proximity.

Under its bolstering haze, he spoke with boldness. “Are you going to prom?” he asked, maintaining some thin sheen of casual inquiry. “I know it’s a few weeks out, but Jenna Horn and a few other people already got prom-posed.”

Madeline gave him the first of many bittersweet, soul-crushing smiles she would come to deliver. “Yeah,” she said, “with my boyfriend from California.”

Ouch! Calvin felt like his heart was Tom the cat, of Jerry fame, blasting his own face with the U-bent barrel of a cartoon shotgun. Prom was one thing, and a boyfriend was another, but a long-distance rich kid Cali guy who was willing to fly out for prom was completely unrecoverable.

“Oh, cool,” said Calvin, before the sting from his blasted-out heart could make its way up to his face and eyes. This was why he never left his PC-lit bedroom, as his buddies loved to point out. “Yeah, I dunno if I’m gonna go. I might just skip it and hit the afterparties.”

“I probably won’t see you at those,” said Madeline, and with violent nausea he imagined her and the Cali hunk rounding bases in a borrowed sedan. Fuck him! This was ridiculous. He wasn’t going to sit here and drag his tender, yearning heart across the coals of her irresistible, untouchable corduroyed legs.

“I should get to class for real,” he said, with all the politeness of a gentleman. “Check out Christina’s World—or don’t. Pics probably don’t do it justice.”

How would he know? It didn’t matter. “Hey, Calvin,” said Madeline, rising to catch him before he could leave with some sort of newfound urgency.

“Yeah?”

She clasped one long, slim hand with the other. “If I don’t see you, don’t think I’m ditching you or anything. We’re moving literally the day after prom.”

“To California?”

“To Nashville,” said Madeline. “My dad rejoined the Air Force after like a billion years of consulting. He says we’ve got to bounce around.”

“I wish I could bounce around,” said Calvin. As he took a few steps back down the schoolside hill, his voice rose to a gregarious volume. “I never go fuckin’ anywhere! But you know what? Christina’s World is in the MoMA in New York, and when I go to college out there I can visit as much as I want! They say you never run outta stuff to do in New York, day or night.”

“That sounds nice,” Madeline smiled, not matching his volume. “Thank you for coming to check on me, Calvin Munn. It’ll be much nicer to have your memory as the sweet boy on the hill than the locker strap dangler.”

Something about the way she spoke turned the knife of heartbreak in his chest with every single syllable. He suffered through it in silence for the last one-and-a-half classes of the day, and only after he poured out his agony to the boys’ groupchat in Ryan Gosling memes did he start to feel better.

The boys, for their part, did not seem to understand or emphasize. “SIMP,” one meme lambasted in reply, accompanied by a distorted doge pointing judgmentally at the viewer with its oversized human finger. A few other members offered brief, lowercased condolences, but Calvin could tell as he read it all that none of them really understood.

That night, when he booted up his PC to attempt to beat Trajan once more, he found for the very first time that Christina caused him sadness. He tried to deliberately ignore the association with Madeline Alder, but it remained, and two days later he relented in switching his desktop background over to Nighthawks.

He saw her twice more that month. The first time was in passing, outside the ceramics classroom with the odd art teacher with the Warhol hair. Madeline came out to use the hallway sink, clay all over her hands and up to her forearms. She saw him, and he smiled, and he looked at the way she had knotted the bottom of her t-shirt to pull tight at the waist. He didn’t remove his AirPods.

The second time was at prom, while Calvin did his obligatory slow dance with ambivalently good-natured Michaela Peters. Michaela was a pal from biology, where the two deskmates had spent the year gabbing about movies and ATVs and anything other than schoolwork. She was big on rough-and-tumble outdoor recreation, and big on a jock she’d known since preschool who’d never go out with a rough-edged girl like her.

Calvin had probably heard ten solid hours of lament for the unrequiting jock that senior year, and he didn’t mind it. He liked to have a girl pal where there was no real risk of messy feelings. It had actually been Michaela’s idea for the two to do prom together, so they could both enjoy a night with their friends without the dubious label of going stag.

Calvin said yes more for her than for him. Anyone seeing Calvin stag would have assumed he just wanted to bro out with the gamer boys in peace. Michaela’s lack of a date, though, would have been cruelly chalked up to her dudelike demeanor and very slight smell of beef jerky.

“You don’t have to do a prom-posal,” said Michaela, but Calvin did anyway. It was just sweet and public enough to show some effort, without being so sweet and so public that it might seem like he had true amorous intent. She cried when she saw the basket of gas station gifts, regardless.

For a stick-in-the-mud abstainer from Polecats school spirit, Calvin liked prom more than he was expecting. He liked getting fitted in the rented tux, cufflinks on his wrists. On a typical day, you couldn’t wear anything nicer than a hoodie in Chester without getting jeers from the local Dollar General set. The license to stunt with impunity for a night was an intoxicating treat.

The music was nasty, which is to say good, and the venue was done up as festive and chic as a sixties-built gym could possibly be. It was all going well until he saw Miss Alder and her date.

He was older, by a couple years, tall and sun-kissed and at ease. She had slid into his TikTok DMs, of all things, and now after six months of texting here he was. His wide surfer’s shoulders dwarfed her, and when his back was to Calvin on the dance floor she completely disappeared behind his frame.

An unrelenting bitterness took hold of Calvin Munn. He started thinking how the surfer probably didn’t know a thing about how to defeat a Roman legion, or how to delight Madeline Alder with a turn of phrase, or how to properly admire the shape of her hands when she was dirtied with clay from ceramics. Worse still, Calvin started ignoring Michaela, and they wrapped up the Billie Eilish ballad without so much as a glance in his partner’s direction.

As quickly as those thoughts came, he fought them off, now and forever after. There was no reason to hate the Californian for dating Madeline. The guy had done nothing wrong, that Calvin was aware of. He sensed with some fright that this bitterness, if allowed to root, would consume him. So, he let it all wash out and dismissed Madeline Alder as a trifle.

“I’m gonna go hang out with Sadie, if that’s okay,” said Michaela, who had been watching this battle on Calvin’s face with utter incomprehension. In contrast to Madeline, she could only understand her lab partner’s meaning if it was spelled out plainer than day. “Thanks again for doing this, and come find us if you want.”

“I’ll probably just kick it with the boys,” said Calvin, ignoring mid Madeline and her strands of near-brown hair and the way her purple dress draped around her collarbones like she was Aphrodite or—Oh, God. He stopped himself from spiraling again.

It was a blessing and a curse that Calvin was not cool enough to get his hands on an illicit flask that night. Spit-tinged Jack Daniel’s might have numbed the yearning, but it might also have sent him plummeting into an abyss of lonesome stupor. Sober, he drank plastic-flute apple cider all night at the tables with the geek scene. They played blackjack for no money and yapped about who was getting grabbed and breathalyzed out on the moonlit quad. At the end of the evening, he got Michaela back to her dad’s car and kissed her goodnight on the cheek. Then he tried very hard not to think about what might be happening some blocks away.

Find Current Affairs by Cairo Smith on Amazon, available in digital and paperback editions.