That Much Is Mine

Fiction: A man sent to find a flower struggles with his nature.

Linnéa,

If a man wears a name long enough, it’ll wear him in turn. He starts innocent. Pathetic perhaps, cowering and whimpering, hiding beneath beds and behind doors. But innocent. He sees the expectations of his name and says to himself: I’ll never be that. I’ll be kinder, quieter.

But pain doesn’t bloom the way you’d will it. It grows up gnarled and wild and thorned. And by the time he feels the cold fear tingling in his hands, and hears his words come out wrapped in barbed wire, it’s already too late.

A man wears a name and the name wears him. And he passes it on.

They used to think a swan wouldn’t sing till it died, that its one and only song would be a eulogy for itself. I went down to the cemetery last week and looked out over the rows of names that used to have men, and I wondered how many songs are buried there too. I looked at the delicate little ruderals growing between the graves, the pastel speedwells and the royal blue Myosotis, and the manicured bouquets people leave. And it struck me how well tended death’s garden is, how only the most delicate little weeds remain.

I know I hurt you. And others, too. I won’t excuse it. I’ve tried to mend what can be mended. Don’t think I don’t feel it. I feel it all.

They’ve got me surveying again. Outside the city. The same roads every morning, the same C-Filter checkpoints. Through the suburbs, through the zones. Every day the same route. Faces behind fences, nameless, standing still in the dust. Fathers. Gardeners. Gamblers. Eyes like fogged glass. No one says a thing. They just watch us pass, and I watch them in turn.

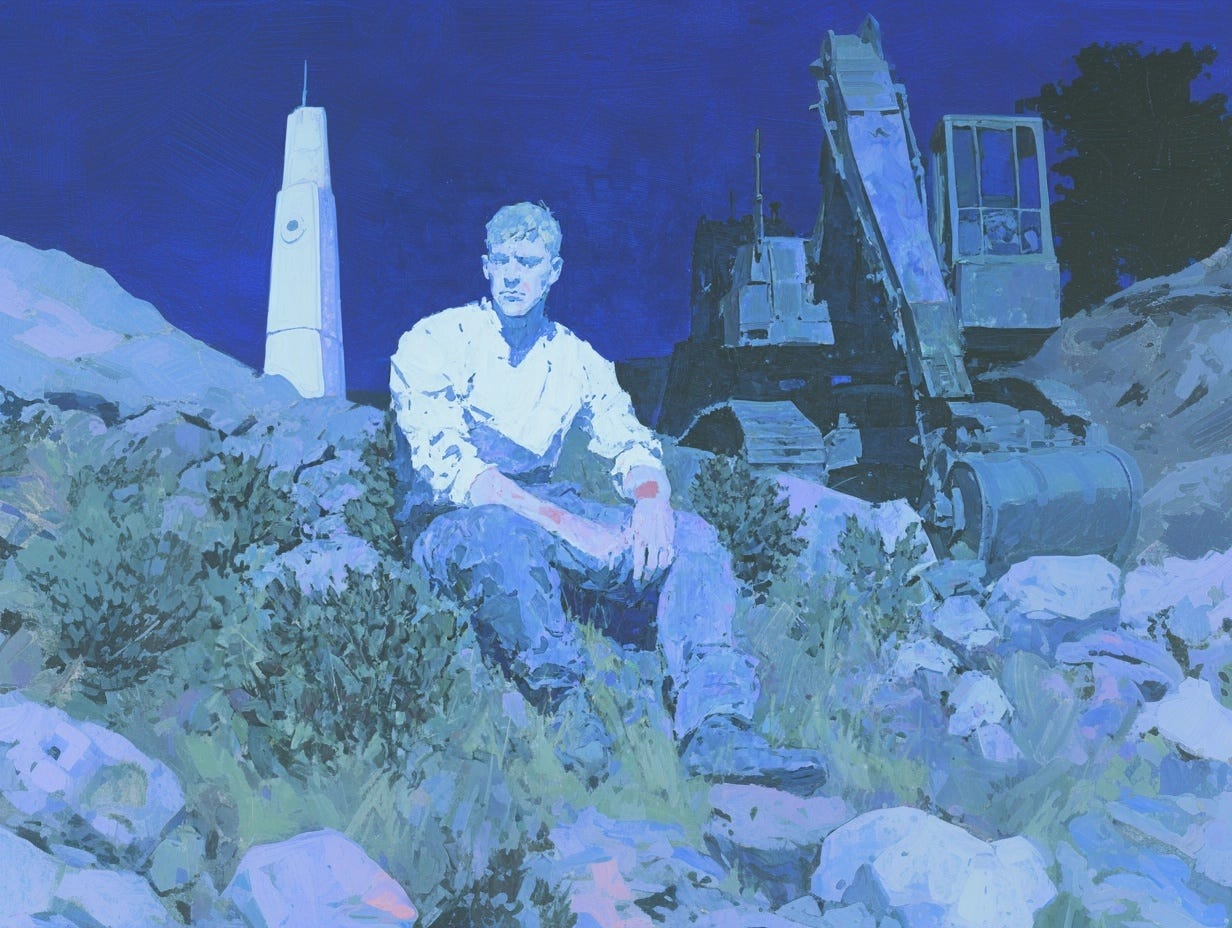

There’s an old quarry about ten miles out, cut into the hills like a limestone scar. There used to be burnt orchid there, apparently. So, they sent me to find it, and I scrambled up the broken faces, and noticed how laboured my breathing was. Dust in my throat. How many of these sites have I seen? They say it’s safe. They pretend. I pretend to believe them.

I sat beside a straggly burnet saxifrage while a cuckoo called from the willows. I felt it reaching out to me, pulling me in, and I tried to shut it out. And the city blurred into the horizon, small and grey and far. The people in it went about their lives, and none of them noticed I’d gone. And the question rose up slowly. I had to ask it out loud. Softly. Knowing there was no answer but needing to give it voice.

Why me?

So many botanists. So many better people. What if I miss it? The plant gone under the pylons, and it’s my name stamped on the loss. And I’d carry it like I carried everything else.

It came back. Meaner this time. I won’t get the treatment. Not with my score. They ran the numbers on the ward. Checked my eligibility. I didn’t ask. Didn’t want to know how bad it was. I’d hoped there’d be more time. But now I know. There won’t be.

I almost missed it. Just a splash of colour between the fescues, half lost in the grass. But I didn’t. I found it. And for once I did something right. That much is mine to keep.

I won’t ask your forgiveness. You’ve every right to hate me. But I loved you. Still do. I looked. I found it. The flower’s still there.

I watched a swan drift across a lake. It didn’t make a sound. And the earth stood still around it, and time had seemed to stop. I watched until it left, and I let the silence sit. Maybe that was enough.

With love,

D